The Legacy of Socrates: A Journey Towards Wisdom

Embark on a profound journey into "The Legacy of Socrates," where timeless wisdom meets philosophical exploration.

The Man Who Questioned Everything

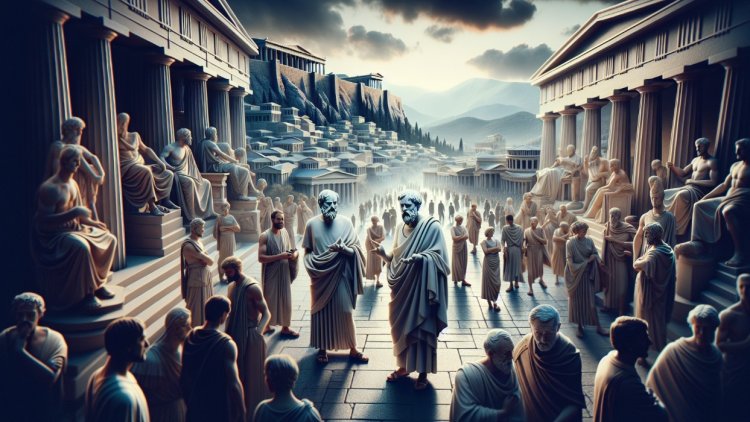

In the heart of ancient Athens, amidst the bustling Agora and beneath the long shadows of the Acropolis, there lived a man whose ideas would echo through the ages. This was Socrates, a thinker unlike any other, whose relentless quest for knowledge and truth would challenge the very foundations of conventional wisdom.

With a sharp mind and an unyielding spirit, he wandered the streets, engaging citizens from all walks of life in profound dialogues. His story is one of courage, intellect, and the unceasing pursuit of understanding—a tale that invites us to question, to reflect, and to grow wiser with each passing moment.

A Different Kind of Journey

In the vibrant city of Athens, where the pursuit of knowledge was as common as the air its citizens breathed, there lived a man named Socrates. Unlike the sophists of his time who claimed to know much, Socrates embarked on a different kind of journey—one that was rooted in the admission of his own ignorance. "I know that I know nothing," he famously declared, setting the stage for his quest for wisdom.

Socrates believed that understanding was not something to be taught but something to be unearthed within oneself. He sought to kindle the flame of knowledge by questioning everything and everyone, including himself. His method was simple yet revolutionary. He would engage with people from all walks of life, from the elite politicians and thinkers to the common artisans and labourers. Through a series of probing questions, he would stimulate critical thinking and self-reflection.

The Art of Dialogue

The art of dialogue was the cornerstone of Socrates' philosophical method, often referred to as the Socratic method. It was through this rigorous form of conversation that Socrates practiced and preached his philosophy of critical thinking and self-examination.

Socrates' dialogues were not mere casual conversations; they were intellectual odysseys. He would begin by posing what seemed like a simple question, but one that invariably led to complex discussions about the nature of virtue, justice, courage, and other fundamental human concerns.

His questions were like a skilled surgeon's scalpel, cutting through to the heart of the issue at hand. In these dialogues, Socrates played the role of the gadfly—a persistent, sometimes irritating stimulant to thought. He would feign ignorance, claiming to know nothing, thus encouraging others to share their wisdom. This technique, known as Socratic irony, disarmed those he spoke with, allowing for a more open and honest exchange of ideas.

A Legacy of Conversation

The art of dialogue was not confined to the intellectual elite. Socrates believed that everyone had the capacity for philosophical thought and that truth could be discovered collectively through reasoned discussion. He engaged with a diverse array of Athenian society—craftsmen, poets, soldiers, and statesmen—and in doing so, he democratised philosophy, taking it out of the academies and into the public sphere.

These dialogues were not only a method for uncovering philosophical truths but also a form of pedagogy. Socrates' conversations were a way to teach others how to think critically and to question their assumptions. He did not provide answers; instead, he provided a way of seeking answers—a way that required rigorous thought and a willingness to admit ignorance and uncertainty.

The Trial of Principles

The trial of Socrates marked a pivotal chapter in his life—a moment when the very ideals he stood for were put to the sternest test. This trial wasn't just about a man, but about the clash between the pursuit of truth and the societal norms of Athens at the time.

The charges brought against Socrates were serious: corrupting the youth of Athens and impiety. His accusers claimed that through his teachings and dialogues, he was leading the young astray from the traditions and values of the city. They also accused him of introducing new deities and questioning the established order of the polis.

As Socrates stood before his fellow Athenians, a jury of 501 citizens awaited his defence. In a display of unwavering commitment to his principles, Socrates chose not to appease the court with flattery or seek mercy through emotional pleas. Instead, he presented a logical and impassioned argument that stayed true to his lifelong dedication to truth and virtue.

The Verdict of Athens

Socrates defended himself by explaining the nature of his philosophy. He argued that, far from corrupting the youth, he was offering them a greater service by encouraging them to think critically and question everything to become virtuous and responsible citizens. He maintained that his actions were not only in the best interest of the city but were also a kind of service to the higher pursuit of truth and goodness.

Despite his eloquent defence, the jury was not swayed. The democratic process that Socrates so often celebrated in his dialogues ultimately condemned him. The vote was close, but the majority found him guilty. When allowed to propose his own punishment, Socrates sarcastically suggested that he should be rewarded for his service to the city. He was steadfast in his principles, refusing to propose a penalty that would compromise his integrity.

The jury was not amused, and they sentenced Socrates to death by drinking a poisonous hemlock concoction. The verdict of Athens was the culmination of a trial that had gripped the city, where the fate of Socrates was to be decided by his peers. It reflected the struggle between new ideas and traditional values, between individual conscience and collective authority.

The Enduring Legacy

The death of Socrates would eventually be seen as a martyrdom for the cause of philosophy. His philosophical teachings did not perish with him; on the contrary, his death became the seed from which grew an enduring legacy—one that would influence thinkers, scholars, and seekers of wisdom for millennia.

Socrates left no writings of his own. His ideas and methods were preserved and disseminated by his students, most notably Plato. Plato's dialogues immortalised Socrates' teachings, capturing the essence of his thought and the vibrancy of his character.

The Socratic method, with its emphasis on dialogue and critical inquiry, became a foundational element of Western education and intellectual tradition. Socrates' approach to philosophy, which prioritised ethical living and the relentless pursuit of knowledge, laid the groundwork for subsequent philosophical movements and for the development of ethics as a branch of philosophy.

Moreover, Socrates' commitment to his principles, even in the face of death, became a powerful example of intellectual integrity and moral courage. His willingness to die for his beliefs has been celebrated as a testament to the importance of standing by one's convictions and has inspired countless individuals to strive for truth and justice.

The influence of Socrates extended beyond philosophy into various fields, including political theory, education, and law. His ideas about citizenship, the role of the individual within society, and the pursuit of the common good have informed democratic ideals and civic discourse.

A Beacon of Understanding

The story of Socrates is a touchstone for those who value the life of the mind and the pursuit of truth. His legacy endures not only in the academic realm but also in the lived experiences of those who seek to lead examined lives.

The Socratic call to "know thyself" continues to resonate, urging us to reflect on our own beliefs, to engage with the world thoughtfully, and to aspire to a life of virtue. In the end, the legacy of Socrates is one of hope—a belief in the power of reason, the potential for personal growth, and the transformative nature of knowledge.

It is a legacy that stands as a beacon for all who believe in the enduring power of human intellect and the unending quest for understanding.

admin

admin